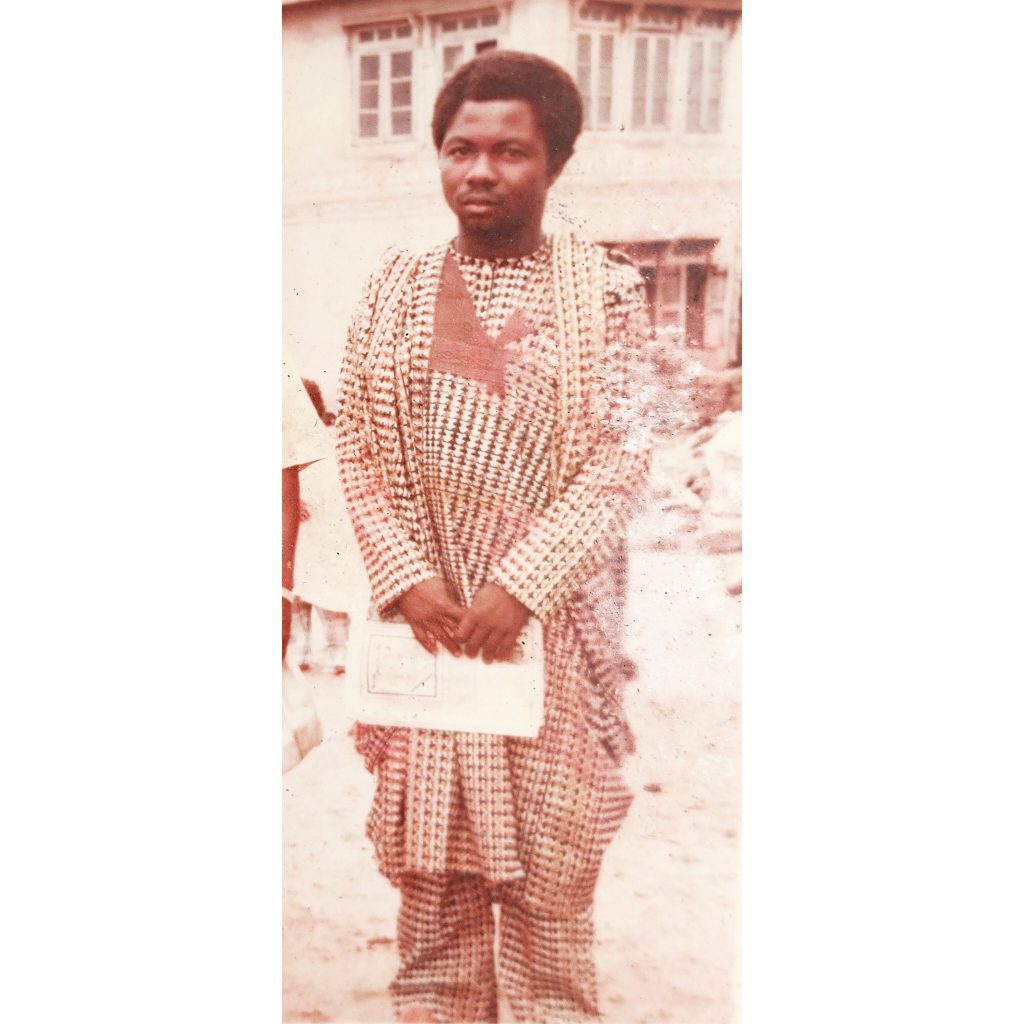

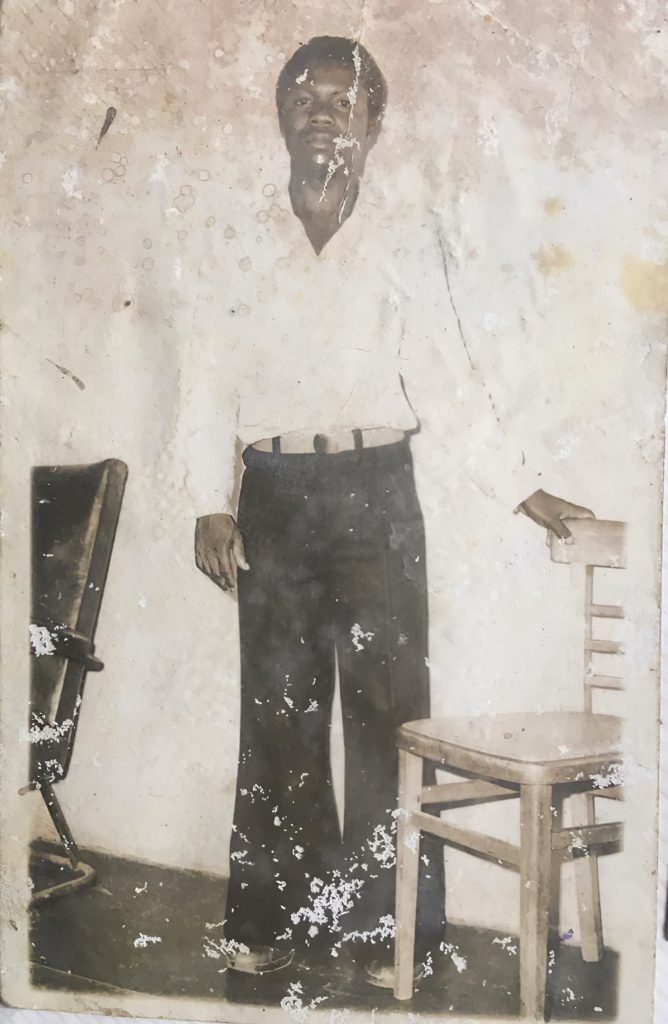

I struggled in deciding whether or not to write this. For many reasons. For one, I do not like making others feel sorry for me. I’ve always found it cringy when people make posts on social media telling the world of their trauma or sickness or whatever it is that’s wrong with them. At the risk of joining that pity party, I almost decided not to write this. Another reason I struggled with this stems from a feeling of shame for not thinking of writing about the subject matter, my father, earlier to publish just in time to mark the 16th anniversary of his passing. But after bouts of internal conflicts, I decided to put pen to paper. I figured writing this would be a cathartic process for me. But more importantly, it would serve as a way to immortalise my father, Soji Olaniyi; a man whose story I genuinely feel deserves to be told.

The second of March is a black-letter day for my family. 16 years ago, my father, R.S.T Olaniyi passed away. At the time, I was 13 years old. But the memories of our last moments have remained vivid. Nothing breaks a young boy more than seeing his perfectly healthy father suddenly knocked down with stroke in the middle of the night. The young boy was not afforded any time to process anything as his father’s health degenerated in quick succession. His father would die three days later. Those three days have remained the darkest moments of his life and though he tries his hardest not to remember the tiny details of the events of those days, they keep escaping like eels from the deepest recesses of his mind.

Growing up, Weekends and Hard Knocks

I grew up not always seeing my dad around. He worked in Lagos and we lived in Ibadan. He came home every Friday evening and left on Sunday afternoons. For the first 10 years of my life, that was the arrangement. There were a few times he couldn’t come home because business was not doing so well. It was until I became older and understood how hard it is to make money I began to appreciate the enormity of his sacrifices. Working five days a week and travelling more than 118 kilometres every Friday and Sunday is the embodiment of fatherly imperative. Perhaps, if broadband internet and Skype existed then, he probably wouldn’t have had to work so hard and he might have lived much longer. Who knows.

Friday was the most anticipated and dreaded day of the week for me and my brothers. We anticipated it because of all the yummy things dad would bring. We dreaded it because mom would always report our sins to him and he wasn’t the type to spare the rod, even for minor errors he should have shrugged off as kids will be kids. He had zero tolerance for stupidity. He was harder on us than most men of his generation were on their children. We loved him at his most doting but also hated him at his most disciplinarian.

Saturdays were technically the only days he had to make up for his week-long absence. As a lifelong educator (he practised as a teacher for a few years before starting Soji Olaniyi & Partnership, his real estate firm), he did his best to make us conscientious. If geniuses were made, with his tutelage, each of his four sons should be one.

Childhood afforded me some grace period while he focused exclusively on tutoring my three older brothers. After eating the most sumptuous breakfast of the week, Saturday morning immediately becomes boring when dad begins his masterclass on grammar. The only thing he used to teach this class was the newspaper of the day. He was an avid reader of The Comet (now called The Nation after Bola Ahmed Tinubu acquired it in the early 2000s). He’d give my brothers op-eds to read and then ask them either to summarise what they read or point out a grammatical error the paper had made and ask them to correct it, especially if it was an error he had told them about before or an error he assumed they should be able to correct. He also taught them idioms and vocabulary they read in the op-eds. He particularly would tell them to pay attention to the context in which those words and expressions were used. If they failed to remember what they should remember, he whopped their asses. While other kids were having fun on Saturday, it was another class with our dad and my brothers hated every moment of it.

But growing up has a way of changing your perspective. When I talk to my brothers about those weekend classes, they confess that dad did a great job and they can’t imagine how they would have turned out had he not been hard on them. They also say he was something of a prophet. He wanted his seeds to be good speakers and writers of the English language so the world would be their oyster.

Ada Boy

Soji Olaniyi was born in 1957 in Oke Baale, a clan in Ada, an obscure village in Osun state. Ada’s only claim to fame is playing host to Miccom Golf Hotels and Resort. When Ada folks talk about Miccom, they say it is one of the best golf resorts in the country. I do not know if they say that as a matter of fact or if they say that to exaggerate the popularity of their home town. Regardless, Ada is an unknown small village, even by Osun state standards. But this small village has produced some of the brightest minds in Nigeria.

Dad’s dad, Falade was a farmer. He had a plantation in a village called Igbajo. Dad often told stories of the harrowing experiences of walking long distances to and from Igbajo. They grew cash crops like yam, cassava, etc. As the first surviving child of Falade, Dad was the eldest of many children Falade’s two wives birthed for him.

He had a tough upbringing and I understand why he went hard on us. No father would want his children to live like that. His father didn’t go to school and he didn’t have anyone show him the ropes. Dad was an autodidact. Relative to his upbringing, we were extremely privileged and it hurt him that we didn’t show enough enthusiasm for education as he would have liked us to. Education saved him from village poverty and it was the only way he knew anyone could succeed. He gave us everything on a platter; things he wished he had while tilling the soils of Igbajo.

He was part of the first set of students enrolled in Ada Commercial Secondary School. He would go on to build lifelong friendships from there. He then would go on to the Polytechnic of Ibadan to study Estate Management. At the time, the Polytechnic of Ibadan was a reputable school, unlike the lair of cultists it has morphed into today.

I’ve only been to Ada once. I went with dad in 2002 for my uncle’s wedding. Me joining him was not planned. After he had finished dressing up, he simply asked me if I would like to join him. It would be the longest trip I’d taken at the time.

I enjoyed travelling with dad because he always paid for my seat to the chagrin of everybody. And every time the conductor or a fellow passenger asked if I was really sitting alone, he would retort by asking: “does it look like he is standing?” They always minded their business after that. Every adult gives their child a lapsit on the bus. It was a way to save some fare. But not dad.

We got to Oke Baale late at night. Perhaps if there was electricity, I could have made a little sense of the scenery with as much visibility emitting from incandescent light bulbs as we snaked our way to our ancestral home in Oke Baale. The house was filled with my aunts, uncles, cousins, and some family members I’d never met. I was left in their midst while dad went inside to talk to his dad and others about the next-day wedding and other family issues.

The next day, I discovered that our ancestral house was built on a rock. One of my cousins bought me some rice from a street vendor at some junction somewhere. It was sold in a plastic bag. That was likely the first time I ate rice from a plastic bag. The rice was saltless and tasteless. I wondered if, in Ada, they don’t salt their food.

Dad left the wedding midway. He tapped me from where I was seated and we walked down to Oke Baale. His father was at home. He didn’t attend the wedding perhaps due to old age. I can’t recall if grandad or someone else served us our meal. But I do recall granddad bringing additional meats for us in a long cooking spoon from the kitchen. I could tell grandad loved dad. We left for Ibadan shortly after we finished our meal.

Hennessey and the Teetotaler

Dad didn’t keep a lot of friends. But the few he had, he’d known them for a long time, either from Ada Commercial, the Polytechnic of Ibadan, or when he had his stint as a teacher at Idi-Ito High School. His friends were a mixed bag. Some enjoyed having frothy beer and piquant peppersoup every other weekend. Others lived either an almost or somewhat teetotaler lifestyle. Dad was somewhat of a teetotaler. His only guilty pleasure was a Spanish wine called Yago.

I recall the first time I got tipsy after I’d taken a few draughts of Yago. I didn’t know that was how being tipsy felt. I told my brother I was feeling a bit funny and sleepy and he laughed knowing what was happening to me. There was a day someone gifted dad a bottle of Hennessey. At the time, I somehow had never heard of Hennessey being mentioned in pop music. It was later in chart-topping songs like Yahoozee I began to hear it mentioned more often. Anyways, when dad brought home Hennessey that day, I was curious to know how it tasted seeing how it was exquisitely boxed. I thought it would taste just as exquisitely. Looking back, it’s almost impossible to believe that dad himself didn’t know anything about the most popular cognac in the world! Otherwise, he wouldn’t have accepted it as a gift.

Dad took his first sip and immediately pouted and grimaced. I asked him what was wrong and he gave me his cup to see (or should I say taste) for myself. I was scared to have a sip. When I finally did, it gave me a sharp sensation. It was instant and it burnt. It was worse on my throat when I swallowed it. When mom heard about it, she threw the bottle away the next day or so. I’ve never had what Dr Gad Saad jocularly calls testicular fortitude to taste Hennessey ever since. That experience made me loathe cognacs.

Dad lived a simple lifestyle. He didn’t wear expensive clothing or designer shoes. Perhaps, the church he attended accentuated his desire to live an unostentatious lifestyle. He went to Deeper Life Bible Church, a church notorious for its puritanical beliefs. Dad wasn’t a puritan. He took wine occasionally and listened to Sir Shina Peters, Ebenezer Obey and his all-time favourite, Kayode Fashola. By Deeper Life standards, he was a sinner. With the perspective of adulthood, I can guess what must have attracted him to Deeper Life. He was enamoured with the oratory of the founder, WF Kumuyi. He probably fell in love with Kumuyi more because he was somewhat a Mathematics genius before becoming a full-time pastor. Deeper Life also does not do posterity gospel and neither does the church monetise prayers or anointing oil and other paraphernalia you tend to find in many churches.

Ota Years

Around 2003/2004, we relocated from Ibadan to Sango Ota, Ogun state. Dad had bought a parcel of land in Ota in the 90s. He bought it for around N16,000 or so. He bought it and abandoned it. It was not until 2002/2003 he began to develop it and he did it fast.

Ota borders Lagos. It is home to a lot of agro-allied industries. It is also home to Olusegun Obasanjo’s farm. It headquarters David Oyedepo’s Living Faith Church Worldwide, a sprawling 60-000 capacity auditorium. There are about six institutions of higher learning you’ll find in Ota, the most in any town in Nigeria (at least as of the last time I checked). But Ota is also notorious for juju. When we moved there, I began to hear stories of Oro. I didn’t even know what Oro was. During Oro, women are not permitted to come out. I heard a legend that a queen transmogrified into one of the trees in front of Olota of Ota’s palace when she came out during an Oro session.

In Ota, we finally got to live as a normal family unlike when we only got to see dad every weekend when we were in Ibadan. When I got in to Iganmode Grammar School, I would leave with him every morning. Again, he would pay for my seat in the taxi. And when he was returning from work, he would stop to pick me up from school and we’d head home together. I’ll give anything to time travel to those days.

Ignamode was about the best secondary school in Ota at the time. It was famous for consistently winning the popular national Cowbell Mathematics Competition both in the junior and senior categories. Though it is a public school with dilapidated structures and amenities, every parent, poor and rich, wanted their child to go to Iganmode. Of course, dad being an absolute lover of quality education wanted me to go to Iganmode. Thankfully, when I wrote the Common Entrance examination, my score wasn’t so bad. I got into a highly competitive school on the merits of my hard work.

At this time, dad began to have his grammar and vocabulary masterclass with me. He did the same thing he did with my brothers. But he didn’t go as hard on me as he went on them. They say parents go softer on their lastborns. He indulged me a lot and I honestly cannot explain why.

It wasn’t just grammar and idioms he taught me. He taught me about the universe, stars, comets, meteors, and eclipses. Dad loved Geography and he instilled that love in me. I remember those long talks we had at night under moonlit skies. We’d talk about everything from myths about the Bermuda Triangle to the Suez Canal. He taught me about Longitudes and Latitudes. He bought me my first Atlas. Seeing how passionate I was about the universe, he suggested I pursue a career in Astrophysics. I can’t deny that I don’t feel ashamed sometimes that I failed him in that regard.

The last discussion we had was on Tuesday the 27th of February, 2007. It was just like every other night. We had our normal conversations after dinner. He showed no signs of any ailment. The events of the next three days would leave my family forever devastated.

In 16 years, I’ve missed a teacher, a friend, and an ass-whopper! He was effortlessly funny and I wish I inherited his humour. His jokes were wild though his impressions were not so perfect. I miss going to church with him. I miss eating Amala from the same plate with him. I miss the grilled chicken and scotch eggs he bought from Tantalizers. At heart, I’m a 13-year-old boy longing for his dad.

Write a comprehensive book about our dad.

I am pleased to inform you that it met my expectations but you need to write a more detailed one.

Love yah

I am really happy to read this, I met him sometimes in 2002, when your brother Tunde olaniyi was in the Polytechnic Ibadan for his A/level. He was a great man.

RIP dad.

Thanks for your words

My condolences, my friend. Well written account as well, heartwarming to read. May his memory always be a blessing, and may he rest in peace.

Appreciate the kind words

Great, what a wonderful dad,your works aren’t in vain. Rest on grandpa.

Manh thanks

What a worthy biography of an Icon! Bro Tunde in those days in the hostel in UNAAB (Now FUNAAB), would never stop telling us how greatly he missed him though he never told us a story so detailed like this one, may be we also never asked! Adieu Great Dad of our great friend…I pray the Lord God Almighty keep everyone of you in the family!

Thank you, Bro Olayemi for exhuming the life story of an hero we have ever longed to see come back to make us regain our joy as family and friends!